The study of Old-English Literature or Medieval Literature cannot be complete without at least hearing something about ‘Waldere’ (or, as some call it ‘Waldhere’). It’s so old that we have very little information about it. But, let’s make the best of it. I’ve tried to compile everything I could about ‘Waldere’ here in as simple words as possible.

So, What’s ‘Waldere’?

‘Waldere’ or ‘Waldhere’ is a heroic poem from the Old-English / Anglo-Saxon period consisting of 2 fragments (called Fragment I & Fragment II) of 32 and 31 lines respectively. ‘Waldere’ is believed to be a part of an unknown Epic.

Whether you’re a Literature student or an enthusiast, ‘Waldere’ is not just important for your studies but it’s a fascinating tale as well! Imagine thousands of years later if somebody finds 2 pages of your random scribbling notepad and they decide to frame it in a museum (maybe trying to figure out more about you!) Quite a thought ha!

| CONTENTS: Introduction to ‘Waldere’ – When was ‘Waldere’ written? Plot Summary of ‘Waldere’: What story does ‘Waldere’ tell us? – Who is Walter of Aquitaine? : Understanding the Pretext for ‘Waldere’ Story – Let’s discuss ‘Waltharius’ for a bit – What happens in ‘Waltharius’? – Important References in ‘Waldere’ – Story in Fragment I of ‘Waldere’ – Story in Fragment II of ‘Waldere’ Literary Elements in ‘Waldere’ – Reference to Christianity – Use of Kenning Why is ‘Waldere’ important historically? Where can I read more about ‘Waldere’? Takeaway |

Introduction to ‘Waldere’

In 1860, E.C. Werlauff (Librarian, Danish Royal Library, Copenhagen, Denmark) found these 2 incredible parchments. Written in Old English, Parchment I had about 32 lines, while Parchment II had 31 lines. Being an important evidence of both Old English Literature and Anglo-Saxon history, authorities preserved them at the same library. They are still there.

The name ‘Waldere’ was given to the two Old-English manuscripts when they were discovered in 1860 in Copenhagen.

Another interesting part here is knowing how only these two specific parchments made it while the rest of the work didn’t! Here’s that little anecdote:

As we will see in the study of the Medieval and Early-Modern eras, people didn’t really understand Old English, at that time. So, for them, these parchments and the whole work were perhaps a useless pile of papers. But these particular fragments were written on sturdy calfskin. So, the bookbinders must have found them useful. They used them to stiffen the binding of an Elizabethan prayer book. Well, thanks to that, we have ‘Waldere’ today! But, it was not so easy.

The author of Waldere perhaps didn’t think about the Literature fanatics from the 21st century like us who would be so curious to find his work. ‘Waldere’ manuscript was poorly written (not semantically, but literally, of course!) It had to be retrieved using UV light techniques.

Let’s quickly answer the preliminary questions about ‘Waldere’ and see where it has come from.

Don’t forget to check out: What happened before & during the Old English Period?

When was ‘Waldere’ written?

After reading about how we found ‘Waldere’, you probably have guessed the answer already.

The precise date when the poem ‘Waldere’ was composed is unknown. But, scholars generally date it to about CE 1000 based on the handwriting and the condition of the parchments.

Plot Summary of ‘Waldere’: What story does ‘Waldere’ tell us?

Waldere is about a hero named ‘Walter of Aquitaine’. (FYI, Here is the meaning of the name ‘Walter’.)

Who is Walter of Aquitaine? : Understanding the Pretext for ‘Waldere’ Story

Interestingly, this same hero, ‘Walter of Aquitaine’ has been featured in many texts other than ‘Waldere’. Here are 3 of them

- ‘Waltharius’ by Ekkehard of Abbey of St. Gall (10th century): Waltharius is a Latin Epic Poem written in hexameters. It is based on our Visigothic hero ‘Walter of Aquitaine’.

- Þiðreks saga af Bern (‘the saga of Þiðrekr of Bern’) (13th century): The main hero of this Old Norse chivalric saga is Þiðrekr af Bern. However, it also tells us stories of many other heroes including the ‘Walter of Aquitaine’.

- Nibelungenlied (~ 1200 CE): This Middle-High German epic poem talks about Walter of Aquitaine very briefly.

There were references to this story of Waltharius & Hildeguth in many more vernacular works across the Germanic Europe. That’s how we know that they were quite popular in the Germanic tribes of Europe.

Let’s discuss ‘Waltharius’ for a bit:

‘Waltharius’ helps us understand ‘Waldere’. In fact, the two works are directly connected. Since we have only 2 pages from ‘Waldere’, ‘Waltharius’ comes in handy here in our studies.

It is believed that ‘Waldere’ is probably an older form of ‘Waltharius’.

The fragments of our Anglo-Saxon epic poem—for such it probably was, and not merely a short lay —show an older form of the story than is found in Ekkehard’s version. Guthhere is “friend,” — that is, king, — “of the Burgundiaus,” while for Ekkehard Guntharius has become Frank. But the story cannot have varied much in its essential facts.

Citation

So, here is a short summary of ‘Waltharius’ (Only the part that is important here)

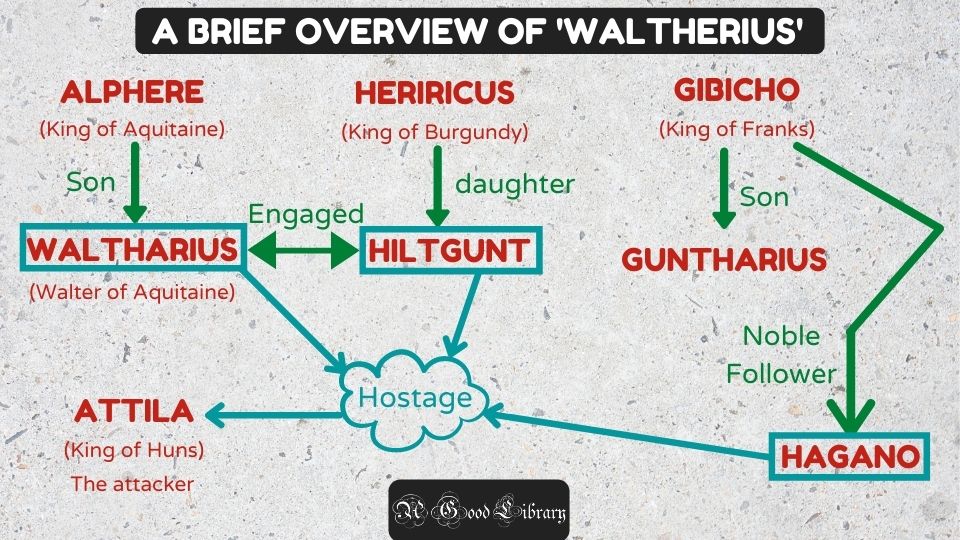

Let’s get acquainted with the characters first:

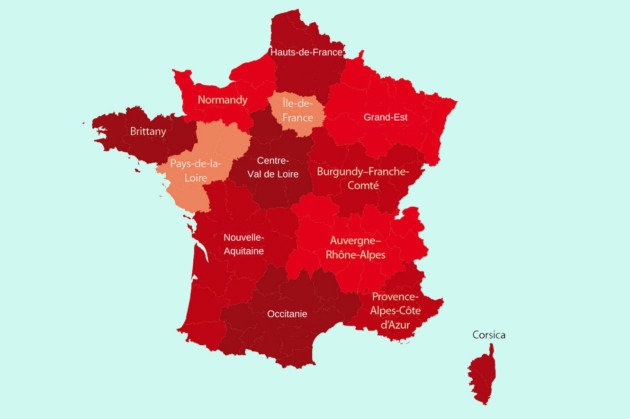

I have also given the maps here so it’ll be easier to understand where exactly things are happening:

Please note that:

Wultherius = Waldere = Walter = Walther

Guntharius = Gunther = Gundaharius = Gundahar

Huitgunt = Hildegyth

What happens in ‘Waltharius’?

- Prince Waltharius and Princess Hitgunt are engaged. But they are still children at this point.

- King Attila has invaded Gaul.

- Threatened by his power, King Alphere, King Herriricus, and King Gibicho have lost hopes. So, they have decided to send their children / honorary members as a hostage to Attila. Alphere sends his son Waltharius. Herriricus sends his daughter Hiltgunt. Gibicho sends his noble follower Hagano.

- They grow up at Attila’s place. (The hostage stuff sounds terrible. But Attila has treated all 3 like his children & trained them well. Hostage ) Hagano & Waltharius have become friends.

- Hagano has become a great warrior. But he eventually escaped to his home when he heard that King Gibicho is dead.

- Waltharius has also become a brave warrior and achieved the post of Attila’s Chief General.

- In all this, Waltharius has still not forgotten the fact that he is engaged to Hiltgunt.

- So, one day, he put together a nice feast for King Attila and the members of the court.

- At the feast, the guests all got drunk and fell asleep. The engaged couple – Waltharius & Hiltgunt – have grabbed this chance to steal some Gold and run away.

- Now they are on their way home. At Worms (yes, that’s a city in Germany), they had to cross the river Rhine.

- Here, the ferryman tattles to Guntharius (who has now become the king of Franks) that the couple is carrying gold with them.

- Guntharius wants that Gold. So, he takes Hagano and 11 warriors with him and they attack the couple who was hiding in a cave. Among those 11 warriors is Hagano’s nephew (sister’s son).

- Waltharius offers a good share of the gold as a peace offering. But, Guntharius wants all the Gold, the horse that the couple was riding, and the bride Hiltgunt too!

- Guntharius tells his warriors to attack Waltharius. One by one, Waltharius, our hero, defeats them all.

- Hagano tries hard to avoid the bloodshed. But, doesn’t work! He now has to prove his loyalty to Guntharius and revenge for the death of his nephew.

- The next morning, when the couple continues their journey, Guntharius and Hagano attack Waltharius together in the open land. Waltharius defeats both of them. All 3 are very injured at this point.

- But, Waltharius and Hiltgunt make it to Aquitaine somehow.

- They get married and live happily ever after.

Of course, there is much more to ‘Waltharius’ than this. (And, the plot is not simple, straightforward like this) But, you get the point.

The reason why we had to go through the rough plot of ‘Waltharius’ is this –

The stories of both fragments of ‘Waldere’ refer to the point before the final attack from Guntharius and Hagano on Waltharius.

But, before moving on to the actual summary of ‘Waldere’ there are some important references in the poem that we need to get acquainted with.

Important References in ‘Waldere’

- Weland’s Work:

In the famous Old-English Heroic Epic – Beowulf, Beowulf himself states that if he dies in the battle, his armor should be delivered to his King Hygelac.

“No need then

to lament for long or lay out my body.

If the battle takes me, send back

this breast-webbing that Weland fashioned

and Hrethel gave me, to Lord Hygelac.

Fate goes ever as fate must.”

(Heaney trans.)

In Old English, he uses the words “Welandes geweorc” which directly translates to ‘the work of Weland”. Weland is a Norse Mythological character. He made these amazing weapons and armor for the great warriors. Since Weland has magical capabilities. So, that made his work even more appealing and special to the Norsemen and Anglo-Saxons of that time.

- Mimming:

(noun) A sword designed by Welland.

- King Theodric:

In the Roman era, there was a tribe of Germanic people who were called “Ostrogoths”.

Remember Attila? During c. 406 – 453, he not only ruled Huns but also served many other tribes such as Ostrogoths, Alans, Bulgars, etc. After his death, his ‘Hunnic Empire’ collapsed, and a new kingdom emerged – this was Amal family’s kingdom. This was Theodric’s family. Thus, we also know him as ‘Theodoric the Amal’. He ruled the Ostrogothic Kingdom during 454 – 30 August 526.

- Widia

Son of Wayland the Smith.

- King Nithad

This king Nithad – cruel king Nithad – appears in many Germanic legends. As you’re studying Waldere here, I am assuming you must have heard at least a little something about ‘Deor’. King Nithad appears in that poem too! The legend of Kind Nithad and Wallend dates back to 7th and 8th-century literature (carved narratives on stones & caskets).

The story in Fragment I of ‘Waldere’:

The story in Fragment I begins with a Lady (someone we don’t really know who) talking or rather encouraging Waltharius for the battle that’s going to happen the next day. Scholars believe that the lady could be Hiltgunt herself. This is based on the premise, that constantly facing and combating all these attacks, Waldere has become hesitant for the first time. He starts doubting himself and his sword.

To summarize in a very simple language, here is my interpretation:

The lady says with full cheer trying to encourage Waltharius, “Welland’s Work is not meant for a failure. It will not betray. The person who holds the powerful Mimming has the power of it. Many times, people have fallen to the ground, shaded their blood & lost lives because of the sword. You – Attila’s Chief general – don’t lose your courage on this day. With brave fight and defense… Son of Alphere, that day is here… When you’ll either win the eternal glory or die.

I’ll never scold your, friend. That dishonor (getting scolded) is not yours. I have never seen you retreat from the fight. No matter how many were against you; you never attempted to run away or save yourself from the attacks. But the more fights you chased, fighting beyond your capacities, I prayed to God that you would not towards the sword’s point rashly (risking your life). (the lady is worried that Waltharius will take a greater fight than he can handle with his resources. Thus, he might fall victim to some aggressive warrior. But, she probably believes that that spirit will help Waltharius here.) As long as God is looking after you, do more and more virtuous deeds and grow your heap of honor. Do not doubt the power of your sword. It was given to you as a gift. Guntharius will meet his fate with this sword (he’ll learn his lesson). As this conflict was created by him (Guntharius) cruelly. He refused the Gold & shiny rings. Now he will turn from this battle ringless (won’t win anything). He must quit and go home empty-handed or he must die.”

The story in Fragment II of ‘Waldere’:

The second fragment starts with someone praising the sword. (It is believed that it was perhaps Guntharius who was boasting of the power of the sword & saying it was better than Waltharius’s) Then, Waltharius praises his own armor. This fragment also features a quarrel between Waltharius and Guntharius. Waltharius is challenging Guntharius to remove the armor that Waltharius is wearing. Here, Waltharius is probably going to the fight. This is how the second fragment goes:

“No other sword is better than the one which is quietly sitting in my sword-holder (the sheath) which is beautifully decorated with jewels. I know, King Theodric had once thought to gift it to Widia along with gold and other jewelry. That is because Nithad’s relative & Weland’s son Widia hurriedly saved him (King Theodric) from some horrible monsters (beasts or animals, perhaps) which he rushed for.”

In the next lines, Waltharius is going to speak:

With the mighty sword (the protection from the danger) in his hand, the courageous & brave warrior, Waltharius spoke, “Sure. you – the Burgundians’ friend – you definitely expected that Hagano would kill me.” (Even though Waltharius is tired of fighting these battles, he believes that he is equal to king Gutherius. Gutherius had hoped that Hagano would break Waltharius down. But, he couldn’t.)

(Waltharius is defiantly challenging Gutherius) “Remove the shield from me – who has become tired of the war – that is protecting my shoulders – the golden, nicely-designed family heritage passed on by Alphere. “It is deserved by the prince. It saves his life from enemies’ attacks. It will always stand by me. When people from foreign lands will attack with their swords, the way you (Gutherius) did, the wise God will still fetch me the victory. If anyone, who leads a virtuous life, keeps faith in Holy God and prays him for support, he will receive it. Then leaders, who rule will give wealth and rewards to that hero. that is….”

Literary Elements in ‘Waldere’

Waldere is characterized as a ‘Historical Poetry’ from the Old English Period in British Literature. Here are a few important literary elements that you can remember easily:

Reference to Christianity

If you noticed in both the fragments, the poet has referenced to ‘God’ and thus, Christianity.

Use of Kenning

Kenning is a literary device that is one of the strongest characteristics of Old English Literature. It is used to describe something indirectly in compound words. For example, the phrase ‘Pool-of-concrete’ means the city.

Here are some examples of Kenning usage from Waldere:

The word ‘help-in-battle,’ is used to refer to the word ‘sword’.

The word ‘Burgundians’-friend’ is used to refer to the word ‘King’

Why is ‘Waldere’ important historically?

We saw that since these two manuscripts were sturdy, the bookbinders used them to stiffen the binding of an Elizabethan Prayer book.

The interesting thing about this “Prayer Book” –

We know that when we say ‘Elizabethan”, it usually refers to England and the Tudor period. But this book was found in Denmark. So, historians believe that it must have traveled to Europe after Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries in England during 1536 – 1540.

Another fact that makes ‘Waldere’ so important historically is this –

“The poem is the only proof that is known that the Anglo-Saxon people had any knowledge of the legend of Walter of Aquitaine.”

Source

Where can I read more about ‘Waldere’?

As we saw, the original fragments are still preserved in the Danish Royal Library, Copenhagen. But here are some online resources where you can get the most:

- The original text of ‘Waldere’ and its translation side-by-side

- Yet another (a bit simpler) translation of Waldere.

- A really good book to study Waldere and other Old-English Poems

- Waldere (Lost Sagas)

- The Old English Epic of Waldere by Jonathan Himes

- The oldest English epic: Beowulf, Finnsburg, Waldere, Deor, Widsith, and the German Hildebrand; translated in the original metres, with introductions and notes by Francis B. Gummere

Takeaway

When we read the two fragments of Waldere, we have that feeling at least one time – “I want to know what happens next!” It is true that English Literature has missed one great epic heroic (& finely narrated) story.